Dicing It Up: It’s Separation Any Way You Slice It!

The adjective "dicey" means involving or fraught with danger or risk, and that’s a good way to describe what happens when Shiva plays. Dice is a game of chance involving small cubes marked with dots (dice). Dice as a verb is an activity that involves cutting things up into little pieces. A single dice is called a die. The word "die" has several other meanings: a device used for cutting out, forming or stamping materials; to cease existing, especially by degrees, to fade; to desire something greatly; to cease operations or be destroyed. (AHD, 2000c, pp. 502, 504) Thus it is fitting that what Shiva chooses to play and play with, also means to cut up into small pieces and also to die, as in death; dice are a perfect thing for Shiva.

The dice game drives the male and female parts of the godhead apart, not only the initial separation from their unity in the androgyne, but their quarreling further divides them. It seems that playing for these cosmic players has tremendous consequences.

This game seems to have literally universal significance. The dice match is in some sense equal to the cosmos, both a condensed expression of its process and a mode of activating and generating that process. If one is God, there is, finally no other game. All the more shocking, then is the fact that he must lose. No wonder that he is sometimes more than a little reluctant to play. (Handelman and Shulman, 1997, p. 5)

Shiva’s dice game is thus “deep play,” a concept Jeremy Bentham, an English economist and philosopher used “to refer to situations in which stakes are so high that participation is irrational” (Hilterbeitel, 1987, p. 470). Why then do they play? One of Parvati’s attendants questions her about this:

“. . . it was wrong of you to play dice with him. Haven’t you heard that dicing is full of flaws . . .” To which Parvati replies, entirely truthfully: I won against that shameless man; and I chose him, before for my lover. Now there is nothing I must do. Without me, he is formless [or ugly—virupa]; for him, there can be no separation from, or conjunction with me. I have made him formed or formless, as the case may be, just as I have created this entire universe with all its gods. I just wanted to play with him, for fun, for the sake of the game, in order to play with the causes of his emerging into activity.” (Handelman & Shulman, 1997, p. 19)

Given that loss and separation are fundamental outcomes of the game producing intense anxiety, one might think that Shiva would think twice about playing, but it seems he really cannot help himself, for he is compelled to play. Handelman and Shulman (1997) explain why, giving four reasons. First of all, if Shiva does not play, the universe would not exist. We are the result of the Cosmic Game. Shiva loses and yet he plays because he must. As we saw before, play is part of his being. Shiva plays because he must, it is part of his nature: “His innerness is infused with play (lilatman)” (p. 185). His very being is play, and he plays because he is a player. He is moved from within in the direction of playing itself, without goal or purpose. The playful impulse is irresistible and must simply play itself out!

Second, the feminine component activates and energizes him in the direction of play, his innerness is moving out. Handelman and Shulman (1997) note that the goddess is less caught up with the negative consequences of play, because she is less in need of being an unfractured whole. She is largely self-contained in her partiality. Third, Handelman and Shulman explain that we "know ourselves only in the context of not knowing" and thus through play we are able to bring different parts "within range of some other form of the god's consciousness and self-awareness becomes possible (p. 187). And last, it seems that the unruptured completion of dense innerness or wholeness is not satisfying, it is unsatisfactory or intolerable and for that reason the Divine restlessly takes itself apart. Essentially it gives Nothing something better to do. The Divine feels at some level that some thing is better than nothing. This echoes Fred Alan Wolf’s (1999) idea that holism has a kind of hunger.

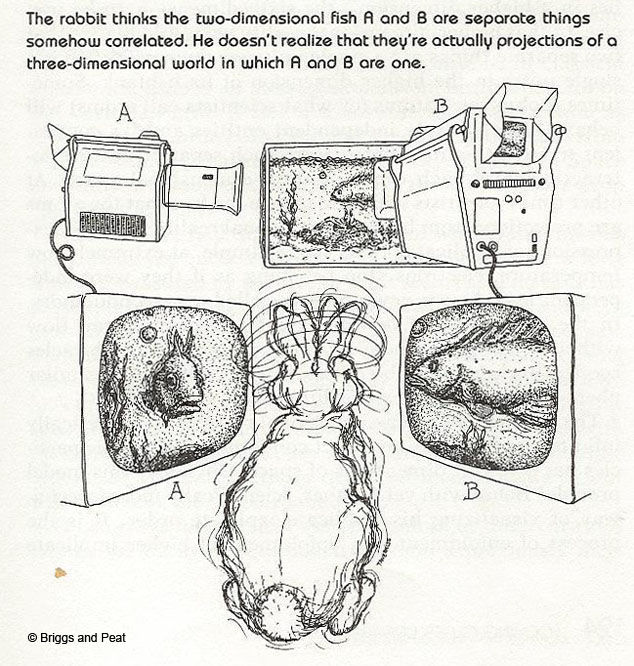

The dice game unfolds in a tricky and subtle process, which is characterized by instability and disruption, and “what is at stake are the continuing reorganization of the cosmos and …the composition and continuous reorganization of the self” (Handellman & Shulman, 1997, p. 7). For the phenomenal world to exist, Parvati must win. So, Shiva and Parvati end the game at odds with one another. The game contracts and fragments Shiva’s being, and while this is a breaking down, it is also an opening up of relationship between cosmic whole and part. Shiva and Parvati see things differently regarding the game. From within the game, Parvati wins, but outside the game it is Shiva. This is reminiscent of Bohm’s Fishtank TV, if we look at it from one way, Shiva is correct that he wins, but from Parvati’s point of view, within the game, it is a different story.

The movement towards internalization and reintegration takes a more torturous and circuitous route. Shiva’s way back to holism is more lengthy and problematic and he never fully achieves wholeness. Or if he does we will never know about it, because we will not be there when it happens! Handelman and Shulman (1997) remind us that “Nothing ever proceeds simply or directly in stories of Shiva, nor is the shortest distance between two points a straight line" (p. 167). The Saiva universe, Shiva’s universe, has a twisted or braided quality “which never unfolds or develops in straight lines. Creation tends to proceed in sudden twists.” (Handelman and Shulman 2004, p. 35)

The Game Itself

What kind of game were they playing? It is thought that Shiva and Parvati were playing one of three different games: Parcheesi, Snakes and Ladders or Cenne (a version of Mancala, which we will not discuss here, because it does not deal with dice). Parcheesi and Snakes and Ladders are both considered “race” games. Race games are characterized as games where you pass successfully along a fixed course from beginning to end, sometimes marked with pitfalls and dangers, and sometimes attacking or being attacked by other players pieces, but ultimately reaching a goal after overcoming hindrances along the way (Bell, 1983). Parlett (1999) points out that the object is to be the first one to get their pieces home, usually in accord with the throw of the dice, and that different theme games are just variations on race games.

Snakes and Ladders is a version of an ancient Indian game called Moksha Patamu, which showed the evolution of consciousness. In the game, good and evil exist side by side. If you are lucky enough to land on a certain virtuous act you ascend to another, higher level, whereas the bad luck of landing on a wicked act would result in descending to a lower level. Two modern forms of the game, based on the ancient versions are: Leela (Johari, 1975) and Rebirth (Tatz & Kent, 1977). In Leela, to begin the game you need to throw a 6, which will put you onto the field of play. Then after having entered the board, basically you move by throwing the dice and moving around the board through different squares and levels. If you land on a particular square, and there is a ladder or spear on it, you get to ascend to the square at the end of that ladder or spear, skipping all of the intervening squares. If you land on a snake, you have to descend to the square at the other end of the snake. To win the game you need to land exactly on the right spot, by the right throw. The modern day Chutes and Ladders (1943) is also a version of this game.

Parcheesi (1867) is a new version of the old Indian game Paschi or Pachisi, which is probably a modified version of the ancient Korean game of Nyout. Pachisi is the national game of India. The board is arranged in the form of a cross, representing the cardinal points, and the pieces travel around the board and at the cardinal point closest to each individual player, his or her pieces can return to the center (R. C. Bell, 1983). This game is probably what Shiva and Parvati were playing. The game mirrors the cosmic pattern of the god fragmenting and reintegrating. Players begin with their four pieces together in a center of the board, called the "char-koni," meaning "throne," with circular areas to the side to hold the completed pieces. Upon rolling the dice and getting the number needed to enter, usually a six, the players enter their pieces, one by one into play. The area of play is marked with individual squares in the shape of a cross with horizontal and vertical axes perpendicular to each other. The cross has three columns and the play proceeds by moving the pieces out from the center and around the board according to dice throws along the two external columns, until each piece has traveled all the way around the board and come back to the last arm, that it descended from originally. At that point, this piece can travel up the final arm to the center of the board, and then be taken off and stored in the circle next to the player. The object of the game is to be the first to reunite all of one’s pieces in the center after traveling around the board, trying to avoid having one’s pieces knocked off, which results in that piece having to start over. Only on this interior portion of the final arm is a piece safe from being knocked off.

The first modern form of this game was called Ludo and was brought to England in 1896, as a simplified form in which all of the pieces begin in the outer circles and end up in the center (Parlett, 1999). Other modern versions of this game descend from Ludo and they are Sorry (1934), Aggravation (1960), Trouble (1965), and the German version Mensch Argere Dich Nicht (translated on the box as Don’t Get Angry), which was commercially introduced in 1914.

The word "mensch" itself actually means "person or soul" in German, while in Yiddish it means a "responsible person." The names of the modern versions show the potential for conflict inherent in the game.

Cosmic Significance

Handelman and Shulman (1997) note that the dice game is model of the cosmos: the dice show the element of chance and the dice throws correspond to the different yugas. Time itself proceeds from this game. Space proceeds from this game as well, for the dice are a model of the cardinal directions in their relation to the vertical vector of the zenith, and the world as we know it, too, and are part of the generative cycle of the game. The numbers on the dice express nearly inexhaustible chain of interconnectedness and parallel diffusion: the realms of space-cardinal directions; time-seasons of the year, cosmic ages; elements that constitute language, elements that constitute the universe, the human body, or consciousness. Time is reflected in the idea of taking turns and space is reflected in the idea of the game board.

This model of the cosmos acts on the very cosmos the model simulates in order to create something new, perhaps unexpected, within the determinate order of the universe. The dice game makes a part of the cosmos become local, creating parts that do not contain the whole. The parts then becomes a reduction, from which the whole cannot be totally reconstituted. The dice game is thus major source of chaos in Shiva’s cosmos, a strange loop that ruptures cosmic holism with unusual consequences. The idea of “sensitive dependence on initial conditions” from chaos theory holds here. Although there is a deeply embedded order in this cosmos, the unexpected turbulence that occurs from some minor incident causes rapid and ferocious consequences, which are unpredictable and non-linear. We cannot predict what will happen next, although eventually everything returns to a somewhat similar order.

Comments